‘Dad’s bipolar disorder rocked family life. I want to help prevent others from going through that heartache’

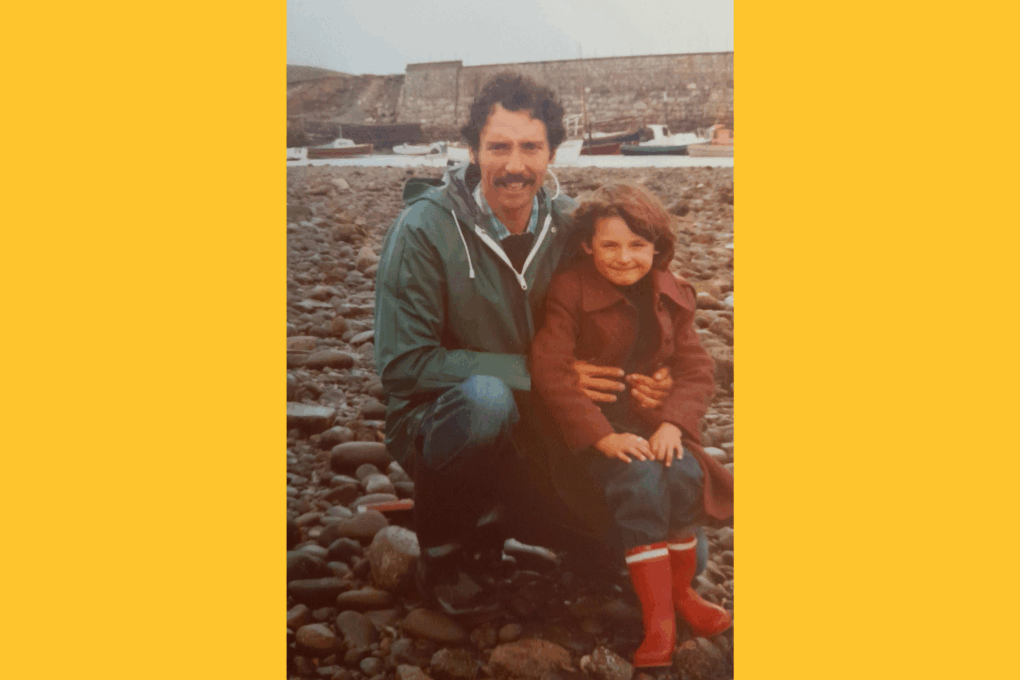

As a child growing up in Lancashire, 50-year-old Lorna Robinson knew her dad, John, had good days and bad days.

Born in 1946, John was never one to talk about how he was feeling. If he was having an off day, Lorna and her siblings just thought, ‘that’s dad’.

“As I got older, I understood more of what dad was going through,” says Lorna. “He’d been diagnosed with bipolar disorder in his 20s and was prescribed medication for it all his life. Although understanding and care for the disorder have moved on massively since then, I really feel it’s still not where it should be.”

That’s why Lorna signed up to Our Future Health – to help improve mental healthcare.

“It’s wonderful that the data set is being looked at in relation to mental health, and not only in relation to physical ailments,” she says.

“I found it so heartening to read the story about the research Professor Daniel Smith is already doing into bipolar disorder using the Our Future Health resource.

“Struggling with your mental health is such a horrible thing. If research like Daniel’s helps people like my dad in the future, that would be incredible.”

‘Dad didn’t talk about his struggles’

“Dad’s struggles with his mental health rocked our whole family,” says Lorna. “We all loved him to bits, but he wouldn’t always take his medication and things were tough. We experienced a lot of heartache.”

Lorna’s parents divorced when the children were young, but the family remained close and supported John as much as they could.

“I believe it is possible to live well with bipolar disorder with the right understanding, symptom management and treatment, but dad didn’t always have this because of the time he lived in. He never talked about his childhood – but we know it wasn’t great – or what he was going through. Plus, health professionals didn’t have the knowledge that they do now.”

Other members of Lorna’s family have also struggled with their mental health over the years. She says this has spurred on her interest in learning about how much mental health relates to genetics, and how much is down to other factors.

“That’s what’s going to be so fascinating about Our Future Health. Researchers will be able to study both genetic and lifestyle factors within the cohort and work out how much both influence someone’s risk of developing various conditions and diseases.”

Geriatric mental health

Lorna remembers her father as a proud man, who enjoyed gardening and spending time on his allotment. But as John got older, his bipolar disorder worsened. He had been prescribed medicinal lithium as a mood stabiliser throughout his life, but this eventually contributed to kidney failure.

“He also experienced the side effects of a cocktail of other medications, and was falling over a lot,” says Lorna. “We never knew whether this was caused by frailty or the medication side effects. Geriatric mental health really isn’t understood enough.

John died earlier this year, in May 2025.

“I kept a diary over the last five years of dad’s life, and he was in and out of various hospitals 15 times with all sorts of struggles. It really is a difficult disorder if not managed well.

“My hope is that more research leads to more understanding, and tailored medications and treatments with less side-effects being prescribed sooner.

“I’d also like to see the continued development of things like talking and family therapies, recovery academies, and support groups.

“It’s so important to prevent bipolar disorder from escalating too far – I hope others won’t have to battle it every day of their lives, as dad did.”

A chance to connect the dots

In the months before John died, he became very depressed. He lost his appetite and stopped wanting to get out of bed.

“By the end of his life, dad’s BMI was 18 and his legs had seized up from not moving,” says Lorna. “He eventually died from the complications – multiple infected bedsores and sepsis – but those were the result of his mental health deteriorating.

“In a way, I was relieved when bipolar disorder and frailty were listed as the cause of death on his death certificate, because that’s what led to everything else. Without them, he wouldn’t have died in the way that he did.”

Lorna notes that it can often be easier to attribute health issues to physical ailments because they’re more visible.

“Our Future Health really resonated with me, because the data set offers the chance for researchers to connect the dots between physical and mental health.

“In cases like my dad’s, you can’t treat one without addressing the other – they come hand in hand. We need to treat people as a whole and recognise how mental and physical health can be linked.

“That’s why I jumped at the chance to join Our Future Health. I want bipolar disorder to be represented in the data set so that health researchers can find new ways to help people manage the disorder.

“Seeing research like Professor Daniel Smith’s happening gives me hope that in the future, deaths like my dad’s can be prevented.”

About Volunteer Voices

Volunteer Voices tell the stories of people who take part in our research programme.

They take part because they want to help improve healthcare for others in the future.

As a health research programme, we are unable to offer medical advice to our volunteers. If you are struggling with your mental health and need support, you can access the following free and confidential services:

- Samaritans – call 116 123 or visit samaritans.org for 24/7 support for anyone in emotional distress

- Shout – text SHOUT to 85258 to speak to a trained volunteer via text for 24/7 crisis txt support

- Mind – visit mind.org.uk or call 0300 123 3393 for information and support on mental health

- NHS urgent mental health helplines – call 111 or find your local service at NHS.uk/urgentmentalhealth

Let’s prevent disease together

By volunteering for Our Future Health, you can help health researchers discover new ways to prevent, detect and treat common conditions such as diabetes, cancer, heart disease, stroke and Alzheimer’s.