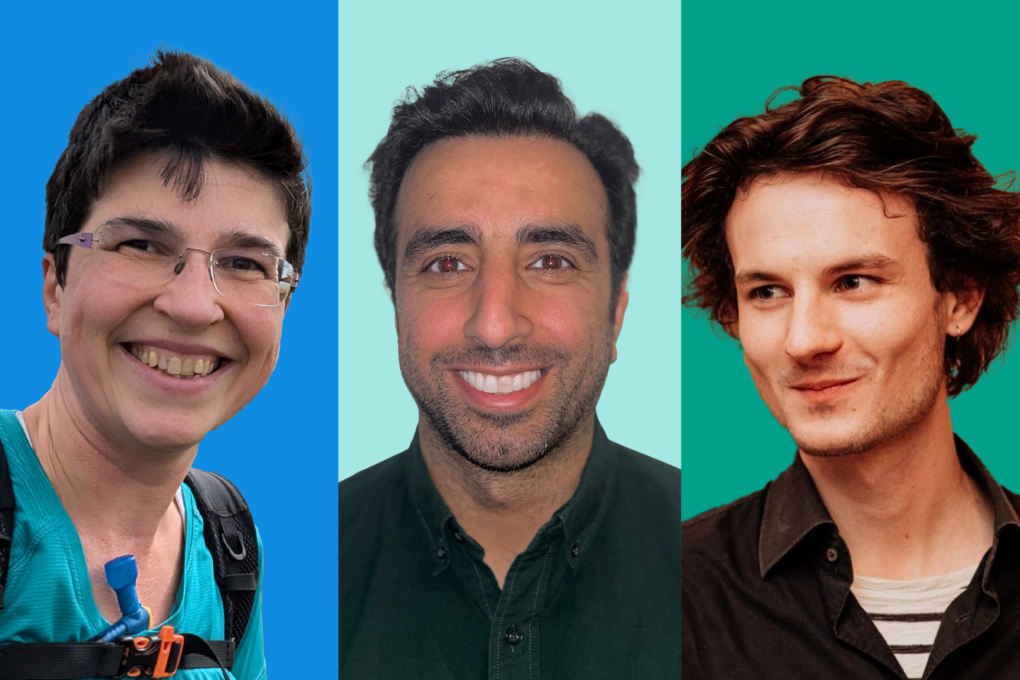

Meet the first researchers who are studying Our Future Health’s data

This summer, we welcomed our first sets of researchers into our Trusted Research Environment (the secure data environment where they can study the information we collect). That means health researchers are now actively using Our Future Health to find new ways to prevent, detect, and treat diseases.

It also means that if you’re a volunteer, you’re already helping their search.

We’ve also welcomed 60 researchers as part of our Early Adopters Programme, in which scientists from academia are granted free access to our data once they have been through our access process. We call them Research Scholars and Ambassadors. They tell us whether they find our systems easy to use, so we can improve them in the future.

So, what will some of these first researchers look for in our data? And how does it feel to be part of this historic milestone in our programme?

Big data, big answers

“I feel a bit like a child in a sweetie shop”, says Dr Katie Marwick, a Consultant Psychiatrist for NHS Lothian and a Senior Clinical Research Fellow at the University of Edinburgh. “The dataset is huge, which makes it very powerful. There are so many cool and exciting things to look at.”

Katie’s research aims to find out how women’s mental health is affected by reproductive transitions – times such as the premenstrual period, pregnancy, or the menopause. “These transitions are associated with an increase in severe mental health problems, in particular bipolar disorder,” she says. “But we don’t really know why. Changes in hormones matter, obviously – but there are also changes in inflammation, metabolism, and sleep.

“All of the big data in Our Future Health will be helpful to understand what makes people vulnerable to having mental health difficulties at times of reproductive transition. For example, the questionnaire that volunteers fill out provides useful information about reproductive mental health. Women are asked if they’ve experienced postnatal depression, or premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). Before Our Future Health, those kind of questions weren’t included in baseline questionnaires of large cohort studies.

“Then there’s the access to volunteers’ health records, such as for hospital admissions, including psychiatric admissions. That will give important real-world insights. We could use the data to look at how risk of hospital admission correlates with reproductive transitions. It may also be possible to use genetic analysis to see if there are any genetic variants that are more common in people who experience mental health issues during reproductive transitions.

“I’m so excited to get started – and to help make the platform even better for researchers like me. I’m looking forward to giving feedback about Our Future Health’s processes and platforms.

‘An unprecedented look at health inequalities’

Dr Mohammad Ali, a Research Fellow in epidemiology at the University of Leicester, is similarly keen to see what new discoveries he can find in our data. His work looks at ethnic health inequalities and how these relate to the risk of lots of different long-term health conditions. These include diabetes, heart disease, and conditions that affect the lungs and kidneys, such as asthma, COPD and renal disease.

Mohammad is based at the Leicester Real World Evidence Unit, which works with ‘real world data’ to analyse the health of the nation. “As soon as I found out about Our Future Health, I wanted access to the data for my research,” he says enthusiastically.

“Our Future Health is exactly the kind of data we work with – but as one of the biggest sources of health data available in the world, it’s on a much bigger scale than other programmes.

“Because Our Future Health has asked people to report their ethnicity, and it’s doing an excellent job of recruitment so that the data is representative of the population, I’ll be able to look at ethnic health inequalities in an unprecedented way.

“At the moment, we don’t fully understand why people in ethnic minority groups are at higher risk of some conditions, such as diabetes. I’m interested in looking at the ‘wider determinants’ of health, which include social, economic and environmental factors. We should be able to see how things like income levels, where you live, educational attainment and employment, all relate to disease risk. “Crucially, as Our Future Health is also linked to hospital health data, it will give us a depth that’s never been available in the UK.”

Research that reflects the UK population

Vincent Straub, from the Nuffield Department of Population Health at the University of Oxford, strikes a similarly enthusiastic note.

“Our Future Health stands out due to its vast scale, encompassing data from up to 5 million adults,” he says. “Using Our Future Health data offers an unprecedented opportunity to conduct large-scale health research that truly reflects the diverse UK population.”

Vincent is exploring what makes people, especially men in early adulthood, more likely to adopt risky health-related behaviours, such as smoking and excessive drinking. “The study that my colleagues and I are working on will examine how these behaviours interact with genetic, family, lifestyle, and income factors,” he says.

“We’re also looking at the effects of these behaviours, beyond the known effects on physical health, for example on things like reproductive health issues.”

Vincent believes that our volunteers’ data will provide new insight into the cause of risky health-related behaviours. “We know that many risky health behaviours are more prevalent in males,” he says. “And we know some people have a higher genetic likelihood of developing addictive behaviours. But how much is this affected by your environment?

“To unpick that question, we can look at people who have shared genetic liability but who’ve grown up in different kinds of environments, and vice-versa. From the information that Our Future Health provides, we’ll know quite a lot about how someone has grown up and other environmental factors, for example their family’s health and educational history, or if both parents were present.

“One related aspect we’d like to look at, is to understand how mental health might be contributing to developing these risky behaviours in the first place. Is there a higher likelihood that someone will engage in risky behaviours if they’ve had had mental health issues, for example, or have grown up in a family where one or both parents experienced them?

“The idea is to generate research that can be followed up in other settings, with more in-depth questions.”

Tip of the iceberg

These three areas of research are just the beginning of what’s to come from Our Future Health – the tip of the future research iceberg. It’s an important step in the right direction, on our journey to help people live longer, healthier lives.

“Our Future Health is a new step forward in health research,” says Vincent. “By bringing together academics from across the UK as Early Adopters, it’s created a group of people who can share research and collaborate.

“There’s already a sense of community between us. We as scientists are meant to be learning from each other, and I’m excited to be a part of that.”

To find out more about our Early Adopters Programme and see the full list of researchers, visit research.ourfuturehealth.org.uk.

Researchers also apply to access our data via our Access Board. You can see a full list of approved studies by visiting HDUK’s Innovation Gateway.

Let’s prevent disease together

By volunteering for Our Future Health, you can help health researchers discover new ways to prevent, detect and treat common conditions such as diabetes, cancer, heart disease, stroke and Alzheimer’s.